The Parthenon, an enduring symbol of Ancient Greek architecture, houses one of the most fascinating and intricate works of classical sculpture: the Parthenon frieze. Created under the masterful hands of Phidias, a celebrated sculptor of the time, this frieze captures the essence of Athenian pride and religious fervor through the depiction of the Panathenaic Procession.

Phidias’ Sculpture of the Parthenon Frieze: An Exploration of the Panathenaic Procession

Phidias, active in the 5th century BCE, was a visionary artist whose contributions greatly influenced classical art. His work on the Parthenon frieze, approximately completed around 432 BCE, is particularly notable for its scale and the level of detail. The frieze, running along the inner walls of the Parthenon’s cella, is about 160 meters long and 1 meter high. It is composed of high and low relief marble sculptures, a medium that was both durable and allowed for intricate detailing.

The subject of the frieze, the Panathenaic Procession, was an integral part of the Panathenaic Festival, held every four years to honor Athena, the patron goddess of Athens. This grand procession ascended the Acropolis and culminated with the presentation of a new peplos (robe) to the ancient olive-wood statue of Athena Polias in the Erechtheion. The festival and procession were significant events in Athenian life, symbolizing civic unity and religious devotion.

Phidias’ depiction of the procession on the Parthenon frieze is a masterpiece of narrative art. The frieze is divided into four continuous sections, each corresponding to one side of the Parthenon. The east side, above the main entrance, shows the climax of the procession, where the peplos is presented to Athena. The other three sides depict the progression of the cavalcade, with the south, west, and north sides illustrating various participants in the event.

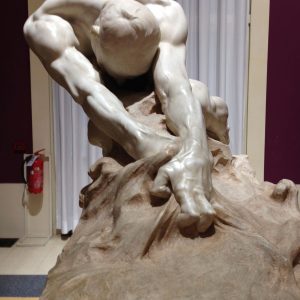

One of the most striking aspects of the frieze is the representation of the human figures and animals, particularly horses, in various states of motion. The sculptures exhibit a remarkable sense of realism and vitality. The figures are not merely static; they seem to move and breathe, their clothes rippling, muscles tensing, and expressions changing. This dynamism was a significant departure from earlier, more rigid Archaic styles and showcased the advancement in understanding human and animal anatomy.

Moreover, the frieze showcases a democratic ethos, a hallmark of the Athenian Golden Age. It depicts not only gods and goddesses but also ordinary Athenian citizens – men, women, and children – participating in the sacred procession. This inclusivity in representation was groundbreaking and reflected the democratic ideals of Athens at the time. Every figure, whether divine or mortal, is rendered with meticulous care, emphasizing the importance of the community in religious and civic life.

Phidias’ technique in carving the frieze was also revolutionary. He employed a combination of high and low relief, creating a play of light and shadow that added depth and life to the figures. The detailed rendering of anatomy, clothing, and accessories demonstrates Phidias’ profound understanding of form and his ability to manipulate marble to achieve the desired effect.

The Parthenon frieze has also been a subject of scholarly debate, particularly regarding the interpretation of certain figures and scenes. Some scholars have suggested that the frieze may include representations of historical figures from the time of Pericles, adding a layer of political significance to the work. Others argue that its primary purpose was religious and celebratory, emphasizing the divine favor and cultural superiority of Athens.

In conclusion, Phidias’ sculpture of the Parthenon frieze is more than just an artistic triumph; it is a window into the values, beliefs, and daily life of ancient Athens. Through the depiction of the Panathenaic Procession, Phidias not only paid homage to Athena and celebrated Athenian piety but also immortalized the democratic and civic ideals of the city-state. The frieze stands as a testament to the artistic genius of Phidias and the cultural zenith of the Athenian Golden Age, continuing to inspire and awe viewers centuries later. Its intricate craftsmanship, realistic portrayal of figures, and narrative depth make it a cornerstone in the study of classical art and an enduring symbol of ancient Greece’s artistic legacy.